After your bullets are sized and lubed or powder coated, you will need to prepare your cartridge cases. There are a number of factory options available as of press time. When I first began shooting 260 most of the factory cartridges I could find locally were Federal with the odd box from Remington. Wanting to press more brass into service without buying pre-made ammunition, I even neck sized a few range pick-up 243 Winchester cases. I didn’t find an appreciable difference between brands until I bought 20 cases made by Norma. In addition to being slightly heavier, the necks grew less than other cases and seemed to give more uniform neck tension. Eventually, I picked up 50 cases made by Starline and I intend to make the same purchase when the cases I currently have wear out. I considered Lapua at one time, but that was before Starline began making 260 Rem cases. Bottom line – pick the brand that performs the best for you for the price you’re willing to spend.

To begin prepping the cartridge cases I will start by applying a light film of Hornady Unique lube with my finger tips on the case neck, and running them through a neck sizing die equipped with a decapping pin to punch out the old primer. The lube is easily removed by a soft cloth after sizing. I use all of my 260 loads in one rifle so do not feel the need to full length size. Additionally, cast loads generate less pressure than standard jacketed loads so are less likely to deform the case as much. You may be wondering about whether tumbling the cases prior to sizing is necessary. For me it is not. My cartridges are used in a bolt action rifle and seldom strike anything but relatively clean concrete upon ejection. A simple wipe around the case neck with a soft cloth to remove light powder / lube fouling is all I do for routine cleaning.

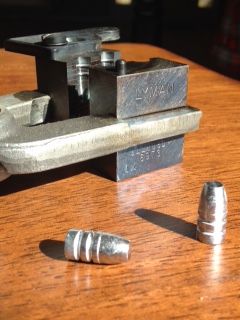

The next step, case trimming, is optional and depends on your specific cases and how many times they have been fired. Most new cases for 260 Rem will be manufactured right around the recommended overall case length of 2.025.” Cases that have been fired several times with cast loads or moderate to strong jacketed loads should be checked for overall length more frequently. Cases exceeding 2.035” in length should be trimmed using a case trimmer or other appropriate device. Chamfering and deburring of case mouths will be necessary after trimming as well to ensure smooth seating of cast bullets.

The next procedures; priming and case mouth expanding, can be accomplished in any order. I prefer to prime the cases first. I do this on a Dillon 550b except I do not rotate the cases to the next station. At this point I’d like to mention primers or the lack thereof. The times we are currently experiencing will pass and large rifle primers will be more abundant. In the mean time, I’ve begun experiencing with large rifle magnum primers in 260 Rem cast loads. I’m down to about 200 standard primers and had a brick of large rifle magnum primers laying around for the past few years. I figured now is as good a time as ever to start testing. While I’m not advocating the practice, I have found no discernable difference switching primers with my cast loads. Then again, I’m operating on the lower end of the pressure scale and its not like these are higher pressure jacketed loads. I want to do more testing and cover my results in a future review.

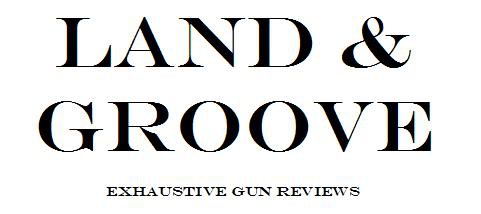

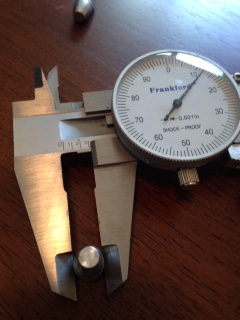

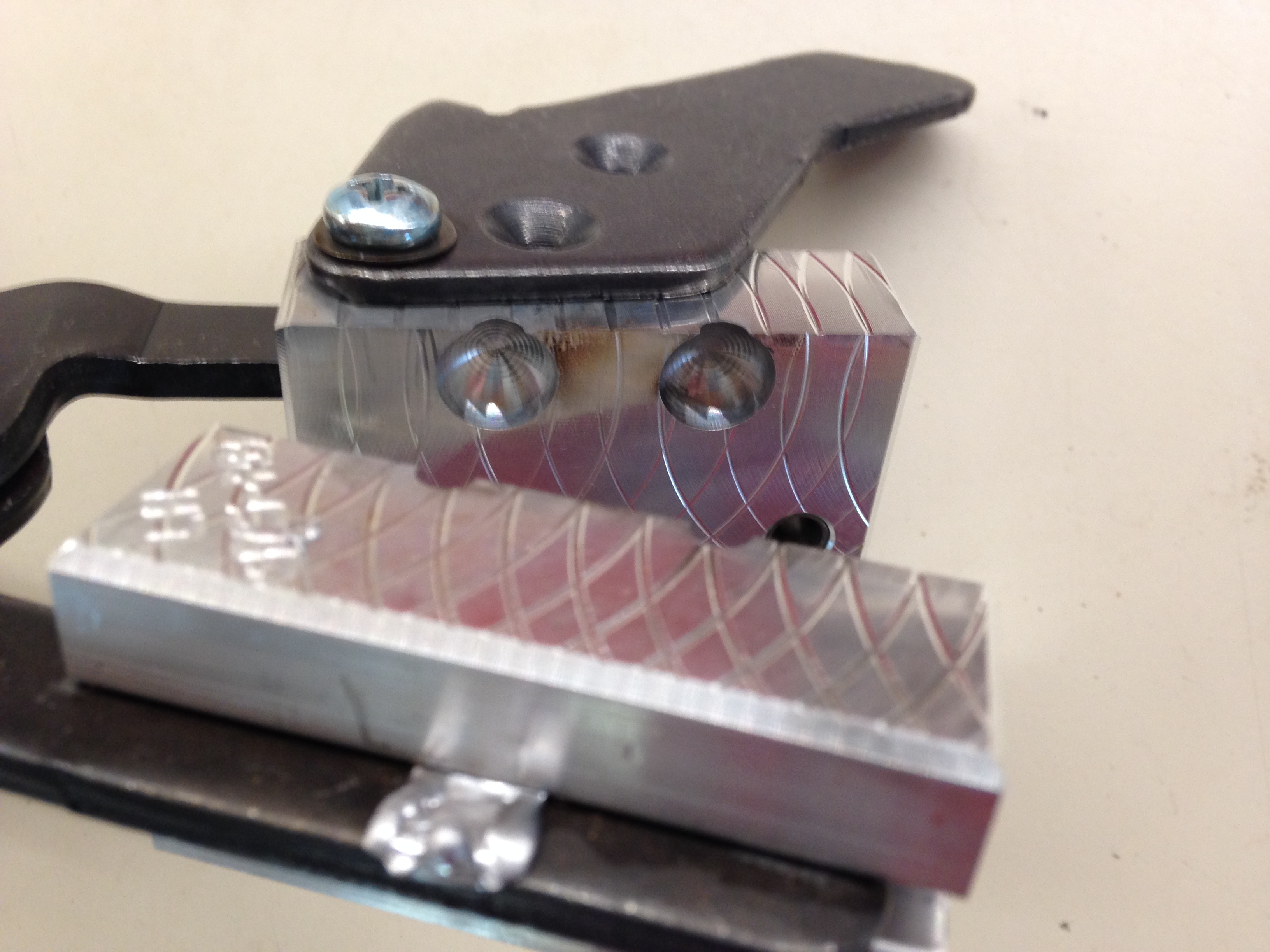

Case mouth expansion is performed at station 2 on my Dillon, which is normally reserved for powder charging. Since I prefer to charge 260 loads off the press there’s no loss of press utilization. I settled on Lyman’s M die, which contains a central mandrel that expands the case neck slightly. It also contains a stepped shoulder which aids in placing a concentric bell on the case mouth. I obtained proper adjustment on the die by raising a case in station 2 without the die in place. I then screwed the die in until it contacted the case mouth. By adding quarter and half turns on the mandrel stem, and checking the case for the proper amount of belling, I was able to fine tune the proper amount of belling on the case mouth. The exact amount of belling is debatable, but I stopped when the base of the bullet just beyond the gas check slipped into the case with hand pressure. I’ll admit that I place a bit more bell on my cases than most but I found that a little too much was better than a little too little as it can result in shaving lead. Keeping your cases trimmed to suggested minimum length will also mitigate over belling. You may be wondering if you could bypass this step in the loading process. I used to think the same thing and couldn’t hit paper at 25 yards. Save yourself some headache and get a proper neck expander die.

And that wraps up Part 4. The next section will cover case charging, bullet seating, and crimping.